Our conventional understanding of the liberal arts is that they are comprised by intellectual pursuits that allow a person to thrive in daily life. At least, daily life as it happened in the era of classical antiquity— which is to say when Julius Caesar was clomping around in his first-edition Birkenstocks.

Then, the pantheon of practical intelligence was comprised of functional understandings in the following fields: grammar, rhetoric, and logic. These were called the trivium, and they were later combined with the quadrivium— arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy.

This collective education was designed to provide its students with the intellectual foundation for more advanced studies in philosophy and theology. The ultimate endgame was to develop a righteous and principled person.

Fast-forward some 2,500 years, and the functional knowledge we use on a day-to-day basis has changed. Sure, we still harness the power of mathematics, but our abaci lay dusty and unused alongside our crowns of laurel and maps of a flat earth. We can still turn our gazes to the night sky, but instead of the naked eye, we now do so with enormous pieces of equipment capable of looking millions of years into the past.

The liberal arts were originally established because they represented the best fields of study for a person who wished to understand the world. Turns out the world changes, and you don’t need a liberal arts education to know it.

Imagine Aristotle, Socrates, or Galileo plopping into an ergonomically designed office chair and logging into Facebook or Twitter. How would those brilliant minds, those forward thinkers, those champions of critical thinking perceive what they found behind the monitor, buried in the depths of the digital sea?

The Internet is as ubiquitous— as present in most of our every day lives— as anything, at any time, has ever been. And advertising, which was of course already prevalent before the Internet arrived, has been revolutionized. Before, advertisements were veritable shots in the dark. Advertisers couldn’t be certain what they were paying for. Would their ads show to an empty room, vacated in favor of a trip to the john, or to grab a frosty beverage from the kitchen? Would their billboards be irrelevant, hovering over highways where drivers couldn’t afford to divert their attention from the high-speed, high-traffic roadways?

The sizes of target audiences were estimated, as was the impact the advertisements had on those audiences. Now, everything is measurable.

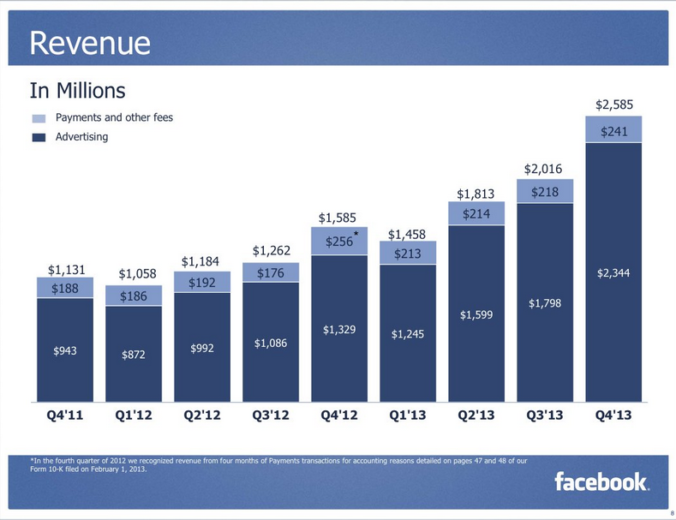

The point here— what needs to be understood— is that advertising is an incredibly vast component of the Internet. The giants of the Information Superhighway, Google and Facebook, earn the bulk of their respective revenues by serving ads.

Google, the veritable beating heart of the Internet, in 2013 was earning as much as 91% of its revenue through advertising.

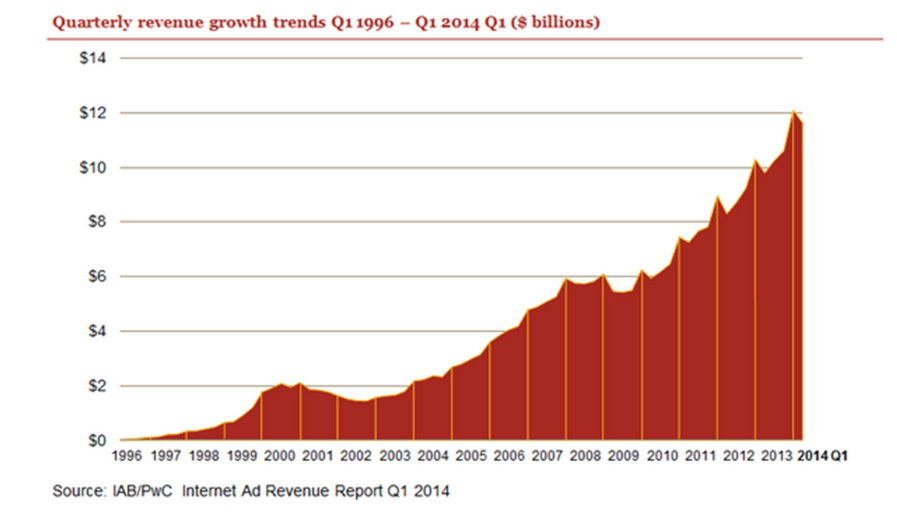

And it’s not just for the worldbeaters that digital advertising has trended upwards. In fact, over the last 18 years, advertising on the Internet has grown from an idea into a $100 billion industry.

So what?

Advertisements are everywhere on the Internet. Obvious or disguised, images or text, you’d be hard-pressed to click a single link without your monitor repopulated with a new deployment of blinking, flashing, strobing advertisements.

The liberal arts were designed to give people an understanding of the world (and in some instances, of the universe). Since the designing of this diverse curriculum, the human population has, um, expanded, and by more than an order of magnitude.

Granted, the following sentiment is perhaps too congratulatory of the human race (and is certainly not made to be reductive of this world’s natural powers and phenomenon), but so much of the earth’s state is a consequence— both positive and negative— of human influence.

As George Carlin so poignantly details (fair warning: explicit content), once we’re all dead and gone, evolved into something else or entirely extinct, the earth will heal itself, undoing the damage we’ve done, and of course no longer acting as the presiding venue for all human activity. But for now— for this cosmic eyeblink that is human existence— we comprise a tremendous portion of what the world is.

And advertising, since its conception, has offered unique insights into human nature.

Advertising reveals trends and tendencies, it illuminates patterns in individuals as well as in groups of people. Advertising serves as a supplement to understanding psychology and philosophy. Anthropologically, advertising provides insight into how the human race constructs the idea of value in our minds, and then interprets it in practice— which is to say, by buying things.

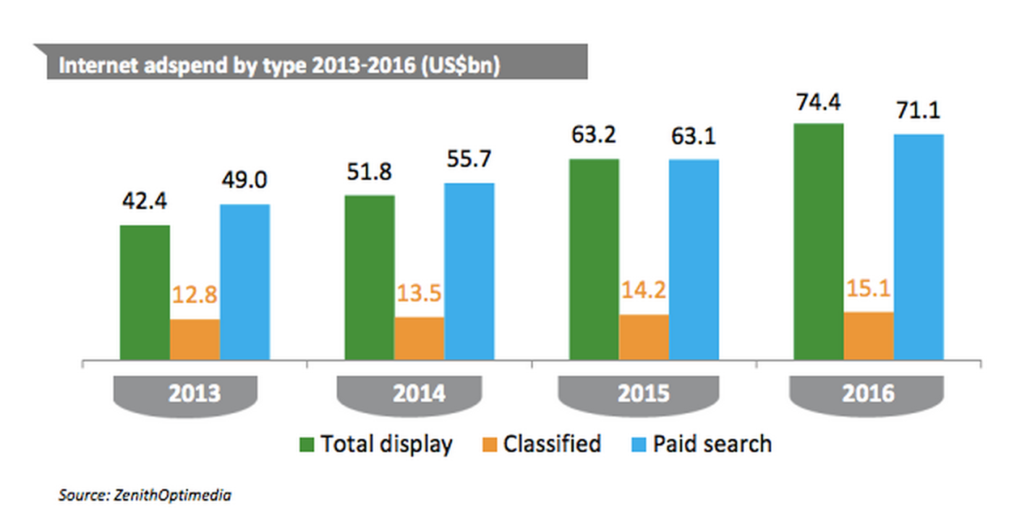

Global ad spend (through all mediums, digital and analog) is projected to grow 5.5% year over year, coming in at a whopping $537 billion. Internet adspend, by comparison, is projected to grow from 2013’s $104.2 billion, to $121 billion this year. That’s 16.2% year-over-year growth— nearly three times the growth of total advertising, which means that digital advertising will continue cannibalizing the pie chart of aggregate advertising (where it’s already taking up a quarter).

Someone could feasibly think, “But how can advertising be this large a part of my life, of our culture? I hardly notice it.”

That’s fair, but it’s also more to the point. Omnipresent entities become easily ignorable— simply absorbed in the fabric of daily living. Just as we do not notice that we blink or breathe until we begin to think about it, we do not notice that at almost any given moment, we’re surrounded by advertisements. We’re simply used to it.

Digital advertising, due to its reach, relevance, and growth, can teach us a lot about ourselves, and about our culture, on both segmented (subcultures) and collective (humanity) levels. This, by and large, is what the designers of the liberal arts wished to achieve.

One does not need to be an astrophysicist to understand the significance of the stars, nor does one need to identify as a philosopher in order to comprehend the value of challenging what we as a society accept as universal dogma. And it doesn’t necessarily take a digital marketer to fathom the potential that the Internet advertising industry has for uncovering hidden truths about ourselves.