Residing in a professional landscape comprised of spreadsheets, tables, grids, charts, graphs, formulas, metrics, and all other manner of impersonalized measurement, it’s very easy to forget who we’re doing it all for.

Human beings.

It sounds a bit dramatic— and on some level perhaps it is— but the humanity of our audiences gets stripped away. Just as the butcher stops thinking of his product as an animal before he swings the cleaver, it’s easy for the digital marketer to forget he or she is serving ads to living, breathing human, with unique motives, personality traits, and interests— not some integer that shows up under the “conversions” column in AdWords.

As digital markers, it’s something of our prerogative to think about our audience as “people who search for [x]” or “people who have been to [x] website”. While this makes sense from a purely pragmatic perspective— this type of generalization helps identify internet-specific trends, which in turn illuminate PPC or CRO optimizations— it culls the very spirit of marketing: the appeal to human impulse.

There’s a balance to be struck between appealing to the human nature of your audience, while still optimizing your PPC account to performance data.

Certain digital advertising methods can betray a sense of impersonality.

Take dynamic keyword insertion for example. Used properly, this can be a fantastic method for appealing immediately to the urgent searcher. Used improperly…well, it might as well be flashing neon sign pointed directly at the end user, saying, “We don’t care who you are as a person.”

See these examples, compiled by Whiteshark Media. Amidst them are some instances of DKI being utilized in improperly organized ad groups. The result? Advertising serving ads with headlines like “Buy Kidney” or “Buy Wife”, with a Display URL that reveals the vendor as Target.

Target’s one heck of a superstore, but they aren’t yet hawking spouses. And for the consumer to whom this ad was served, the advertiser is suddenly about as attractive as a green-toothed panhandler.

Purchases, leads, conversions en masse, are completed because the end item— whether that item is a material object or service, as will usually be the case for a purchase, or more abstract— like the promise of more information, sometimes provided in the form of a whitepaper, eBook, or other asset— possesses value to the converter.

And here’s the other part of the equation. Even something as seemingly cut and dry as the idea of value is abstract, in the sense that it means something different to everyone.

Value is a fickle thing from the eyes of the advertiser— even marketing a static product, how you market it can determine the difference between a conversion and an empty impression.

For search engine marketers in particular, this distinction can be made in the 70 characters of description ad copy we’re afforded. Probably the more common methodology of pitching a product is to list its features— which is to say, what the product boasts for itself.

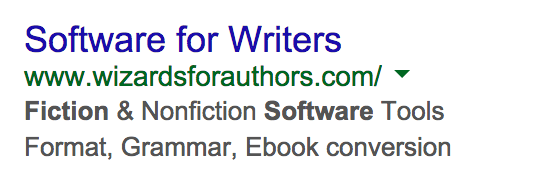

Here’s an example of a feature-oriented pitch, in an ad served after searching “novel writing software”.

Notice that there’s nothing here about what might benefit the user. Sure, we see some fancy elements of the product— it’s obviously designed to format documents correctly, to correct grammar, and to provide functionality from a normal word document into an Ebook document, such as .epub.

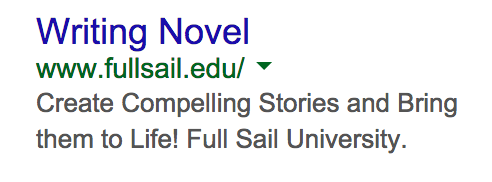

But let’s look at a different angle, this one provided by for-profit education champions, Full Sail University.

Never mind the fluky headline— the description line tells the user (an aspiring novelist, evinced by their “novel writing software” query) exactly what they want to hear: by clicking on this link they’re going to learn how to create compelling stories, and how to bring the contents in to life.

That’s exciting. That’s action. That’s earned my click.

Zoom out for a moment and think about the query “novel writing software.” There are plenty of components to that. It’s possible someone with a completed novel searched on this term, looking for a program that could easily transition their Great American Novel from a word document into something easily grokkable by anyone with a Kindle.

That person would have clicked on the feature-laden ad— the one with the “Ebook conversion” messaging.

But the whimsical beatnik with a half empty bottle of red, a full ashtray, and a trash can full of crumpled beginnings? That second ad, the one that tells the user— the human being with interests, goals, passion—how they will benefit, how their personal fascinations will be advanced— gets that click.

Neither method of advertising is better or worse. They both have their advantages and disadvantages. But don’t lose sight of one in favor of the other. Just remember that no matter who your audience is, they’re a diverse group, and one set of messaging will never reach them all.