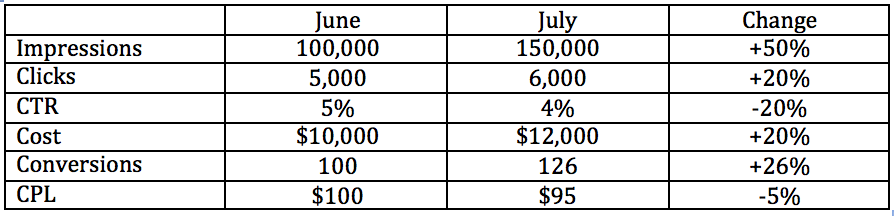

Many reports ignore net gains by presenting data in some variation of the format:

This table does a decent job of showing performance (of course there would be more metrics like CPC and conversion rate) but it doesn’t make it very clear what the cost of the change in performance was. By that I mean, what were the net gains (or losses) between June and July.

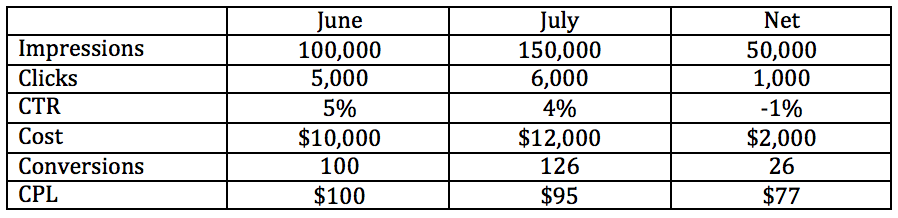

This is sort of incrementally, which I am a big fan of, but more simple. The idea isn’t necessarily to show incremental gains, but rather show the business owner or online marketing manager or CEO or CMO or whomever, what the cost was for the increase or decrease in performance.

This chart now shows that you bought 1,000 more clicks and 26 more conversions for $2,000. That means those extra clicks and conversions were actually significantly less expensive than the first 100 conversions for the initial $10,000. ($77 per lead/sale compared to $100 per lead/sale). The extra $2,000 was very wisely spent and made a positive impact on the account as a whole.

When framing data in a more accurate way, you are much more likely to have an ah-ha moment with the client where they see where the extra budget is going and the value it’s creating. The same if they cut the budget. They’ll see the impact more directly and can make a better decision on if the new lower budget is right, or if they should revert back to the previous budget.

It is my belief that we ignore net gains for two reasons.

1. We don’t think this way. We’ve trained ourselves to think in percentage change versus net gains; a simple thing to fix.

2. It’s more likely, because of the clarity net gains create, that a negative outcome of reducing budget or being pushed about drops in performance will occur when the net gain is actually a net loss. This is harder to understand but more important. Covering up results, or lack thereof, even unintentionally is bad for the business, the relationship and the forward movement of the account.